The nonprofit starvation cycle and how to help charities avoid it

A myth has been circulating around the nonprofit world for decades, and it's time to debunk it.

A myth has been circulating around the nonprofit world for decades. It goes like this: A charity is only worthy of our money if it spends very little of it on overhead expenses. After two years of global crisis and a rocky financial year for many, it’s time to debunk this myth and change the way we look at non-profit organizations.

The truth is – and research has shown that – nonprofits that invest in capacity-building – things like technology, financial systems, skills development, and fundraising – are more likely, not less, to succeed.This is not news. We know this to be true of just about any organization.

Yet a general rule of thumb still used by many charity-rating organizations is that the best charities spend 25 percent or less on overhead. And, because the myth that low overhead is the mark of a good charity never seems to fall out of fashion, donors want to see this number continue to decrease.

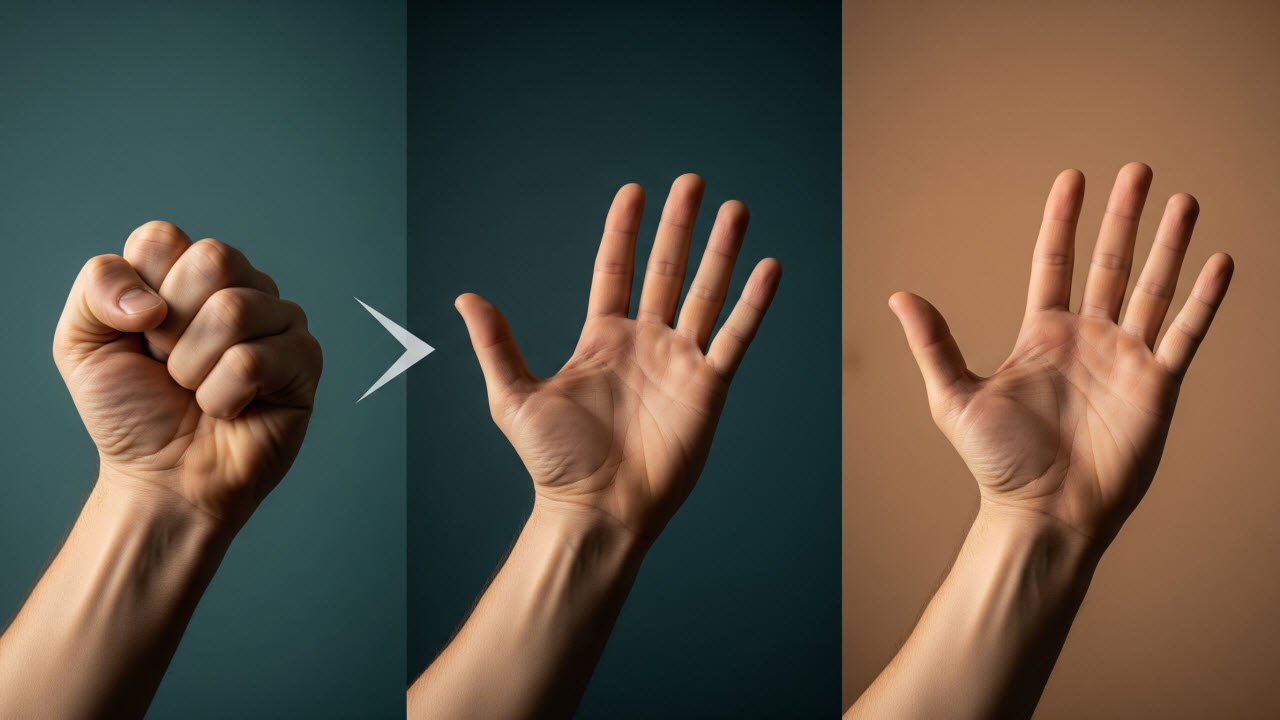

A 2012 donor poll conducted by Grey Matter Research showed givers believed a charity should not spend more than 22 percent of its budget on overhead. By 2018, the same question revealed givers preferred overhead spending be 19 percent or less. The result has been charities deprived of money they need to function. Conforming to expectations of constantly lowering overhead expenses can be a downward spiral. It’s known as the “nonprofit starvation cycle.”It begins when givers have unreasonable expectations about a nonprofit’s needs and spending. Nonprofit leaders feel they must decrease spending or lose givers. Other nonprofits in the same sector lower their overhead for the same reason, compounding the problem. Infrastructure is neglected, and nonprofit leaders are tempted to produce misleading reports the next time they present to givers. After succumbing to the pressure, charity leaders may face more unreasonable expectations again the next year.

What these givers may be missing is what happens when money is poured into programs without the systems in place to sustain them, without the computers needed to produce givers reports, without the staff needed to hold fundraiser events. The list goes on and on.

It is no surprise that turnover rates in the non-profit sector are higher than average. (Research in January 2020 from the company Nonprofit HR reported that 45 percent of non-profit workers were looking for another job, the majority of them outside the non-profit world.) So, what is the right amount for a nonprofit, ministry, or charity to spend on overhead? Well, it depends on the charity.A food pantry, for example, may not require much overhead, while a charity conducting medical research or a ministry spreading the gospel through high-tech media may need to spend more on things like equipment, facilities, or training. For these, cutting overhead might quickly put them out of business.

Which charities may be most hurt?

Most agree that the non-profit sector is fairly resilient, having grown consistently over the last two decades, accumulating a collective $1 trillion in net assets and having endured two years of a global pandemic. But the collective picture masks the struggles of smaller nonprofits, which were harder hit in a COVID-impacted economy, researchers at Candid report.These smaller charities (which include many education-related charities, as well as crisis-intervention and mental-health nonprofits) may suffer the most if forced to cut costs at a time when they’re being asked to increase the number of people they serve.

And if they just can’t make the numbers work any longer, they may find themselves left with one option: shut their doors on the people they yearn to serve. “But the people served by shuttered nonprofits face practical consequences that cannot be abstracted away,” Candid says.

There are ways you can be wise with your gifts without furthering the myth and perpetuating the nonprofit starvation cycle.

5 types of questions that can encourage a charity and help you give more wisely

How can you know if a particular nonprofit is a good investment of your charitable dollars? There are better ways to judge than just overhead. Consider taking a step back and getting to know them a little. Then your questions can make you not only a wiser giver, but also a more understanding one.

There is great benefit to getting to know the charities you support. If your goal is to help, they will likely appreciate your support and interest, and you may find they welcome your questions.

Building these relationships makes false measures of success, like the myth (low overhead=good charity), unnecessary and your experience as a giver more rewarding. And you’ll have done your part to end the nonprofit starvation cycle, perhaps once and for all.

Image used with permission.Related Articles

August 17, 2025

When Giving Becomes About Us

Have you ever felt a quiet sense of pride after giving, like you were just a little more faithful than others?...

August 10, 2025

Giving as Worship, Not Leverage

When our generosity becomes a tool for control, we cross a line. In church life, it manifests more than we might expect....

August 3, 2025

When Giving Feels Like a Burden

Several common but harmful motivations for giving might sound spiritual on the surface, but actually miss the mark of bi...